Many people wonder what exactly happens in the body during cold plunging. In this article, we look at the most important physiological, i.e., physical, aspects. When you begin cold plunging, you should be able to feel and understand these effects directly on your own body.

Table of Contents

3 Primary Effects of Cold Plunging on the Body

During a cold plunge, three primary reactions occur in your body as a direct response to exposure to the cold. We will go into these 3 reactions in more detail below:

- Peripheral vasoconstriction

- Chemical thermogenesis

- Mechanical thermogenesis

1. Peripheral Vasoconstriction

This term sounds complicated, but anyone who has frozen properly should know it. The peripheral parts of the body, i.e., the parts of the body that are furthest away from your heart and therefore the most difficult to keep warm, are “sacrificed” by the body. This is a very natural and sensible defense mechanism, as it greatly increases your chances of survival. Instead of saving the entire body, only the most necessary parts with the most important organs are saved. And that doesn’t include your toes, feet, fingers, and hands.

You probably know from your own experience that you have cold hands or feet in winter. This is peripheral vasoconstriction in miniature. For example, if you are out and about in winter wearing light clothing, your hands and feet are usually the first to get cold and start to sting uncomfortably.

Peripheral vasoconstriction is therefore a sensible defense reaction of your body to cold, in which the blood vessels in the peripheral regions of the body, i.e., in the arms, legs, hands, and feet, are constricted and the blood flow in these areas is reduced as a result. This means that less warm blood reaches the surface and therefore less heat is lost. You notice this particularly well in a cold plunge, as your hands and feet start to really hurt quite quickly. Some ice cold plungers also complain of numbness in these parts of the body if they stay in the ice bath tub for too long. The reduced blood flow to the skin leads to a pale or bluish discoloration of the affected parts of the body, as less blood and therefore less oxygen and nutrients reach them. This is a problem if it lasts longer. However, with a short cold plunge lasting a few minutes, this usually doesn’t matter.

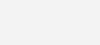

You will see many ice bathers adopting poses like the one below to better protect their hands. You can’t do this with your feet, of course, unless you’re wearing neoprene socks or shoes.

2. Chemical Thermogenesis

The first step is that the body decides to no longer keep all parts of the body warm, but only the vital organs in the center of the body. However, this alone is not enough, as the body must also try to boost heat production to warm itself up from the inside. This happens through biochemical processes such as the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. The cold activates the sympathetic nervous system, which promotes the release of neurotransmitters such as noradrenaline. These neurotransmitters act on various target organs and tissues to increase energy production and metabolism, which leads to increased heat production.

The body has two types of adipose tissue: white adipose tissue, which mainly serves as an energy store, and brown adipose tissue. Brown fat is particularly important for thermogenesis as it contains a high number of mitochondria, which can produce heat themselves like small power stations. When the body is exposed to extreme cold, brown adipose tissue is activated and begins to burn fat to generate heat.

Children naturally have more brown fat to stay warm without shivering. Unfortunately, many adults usually have less, but regular cold plunges can stimulate the development of new brown or beige fat..

The good news is that brown fat, or beige fat (an intermediate form), can be produced again when it is needed. However, as we no longer expose ourselves to sufficient cold stimuli in our modern world, brown fat is no longer produced or is not present in sufficient quantities. However, it is produced if you go ice swimming regularly. Certain proteins, such as Uncoupling Protein 1 (UCP1), which is found in the mitochondria of brown adipose tissue, also support the process of thermogenesis. UCP1 is involved in the uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, whereby energy is generated in the form of heat instead of ATP (adenosine triphosphate).

3. Mechanical Thermogenesis

What sounds pompous means: shivering. We all know it – when we are cold, we start to shiver. The cold stimulates the nerve cells in the skin and sends a signal to the brain that it is cold. The hypothalamus in the brain then initiates the activation of the muscles. The large muscle groups, such as the trunk and limbs, are particularly important and start to shiver rhythmically. You cannot avoid the shivering or control the process, as it is automatically controlled by your brain.

The trembling of the muscles generates frictional heat, as if you were rubbing your palms against each other. The heat is a by-product of friction, so to speak, so a disproportionate amount of energy is used to get you warm. This has the pleasant side effect that you also burn calories and can lose weight by cold plunging.

The energy for shivering comes from your body’s carbohydrate stores, which are available at short notice, and from fats (white fat). The increased metabolism also contributes to heat generation, i.e., the engine is started and begins to tremble, which consumes energy, but the fact that the engine is running at full speed also warms it up.

Conclusion

As you can see, your body is remarkably adaptive and resilient. And you need to treat it with the same care and attention. It can usually do more than you think. A short, well-timed cold plunge challenges your physiology in powerful ways; from protecting vital organs, to generating heat through fat metabolism, to burning energy via shivering. With regular practice, these responses strengthen over time, helping you become more resilient, energized, and adaptable to stress.